Genetically Engineered Humans

- Amelia Papi

- Dec 11, 2018

- 4 min read

Updated: Dec 12, 2018

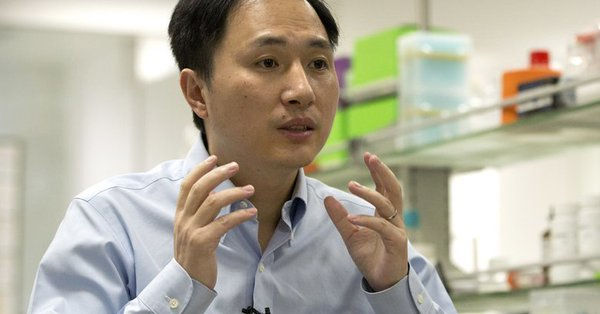

On November 28th, a Chinese scientist by the name of He Jiankui announced the birth of twins he genetically engineered to be HIV resistant. It is not known if he obtained the parent’s consent, or if he is even telling the truth. In the United States, genetic manipulation is prohibited, but the laws in China aren’t as black and white. This is the first case of CRISPR technology being used for human modification and it has taken the scientific world by storm in an ethical debate.

CRISPR-Cas9 is a collection of enzymes and genetic guides used for editing DNA. Typically, this biotechnology is used for the modification of somatic cells, the nonreproductive cells that make up an organism. Contrary to normal usage, and where the debate lies, is that the scientist edited the germline cells of the twins, which gives them the ability to pass their altered DNA to offspring, something the somatic cells are not capable of doing. Currently, the month old twins are showing differing reactions, as one does not seem to be HIV resistant. It’s been hypothesized that this was done on purpose, that one twin was selected to be used as an experimental control. However, no information has been able to be confirmed as Jiankui has not posted his work.

Recently, a panel discussion was organized at WPI to address the concerns and topics of CRISPR usage on humans. Julia Dunn, a senior BME student who attended the panel, was readily available to share her opinion on the matter. One thing she stressed was the importance of consent in this situation. This is because the girls will forever be treated as science projects, but can also only be tested with the parent’s consent and theirs when they’re of age. Dunn strongly believed that germline editing should not be allowed in humans. There are too many variables and not enough information to make an impact. She also emphasized the relationship between socioeconomic status and a possible future of ‘designer babies’, stating that communities most at risk for the disease may not be able to access genetic treatments simply because of wealth or location. This profitable market leads her to ask the question, “who decides what should be prevented?”.

Wanting to hear more from a panelist, I talked to a professor of Biology/Biotechnology at WPI, Reeta Rao. Her focus was not as heavy on the ethical concerns, but rather the fundamentals of the experiment itself. At its core, the experiment is flawed for a few reasons. Yes, the scientist broke rules and went around his team and the parents, but the reason why Rao is baffled is that there was no reason for him to actually do this experiment. “The one problem for me is that it was not even necessary. He just did it because he could.” The whole experiment is faulted at its core. As a scientist, this is what bothers her. Rao is all for and furthering science and medicine, but she believes there was no need for this.

Jiankui used CRISPR to make the twins HIV resistant. Without going too in depth about the process, there are two types of the HIV strain, and he only made them resistant to one. Theoretically, they could not contract one type, but still be able to get the other. The reasoning for choosing this set of twins is also flawed. Their father had HIV, but because the twins were conceived through IVF, they would not have been exposed anyway. We also have no idea about the potential off-target effects. Testing in mice has shown many more off-target effects than in a test tube, but now that the twins are born, we have no way of telling if they have these side effects.

CRISPR, however, is not all bad. It is, in fact, a great piece of biotechnology that Rao herself uses in her lab’s fungal research. But, she says she wouldn’t implement her work in humans. She did inform me of plenty of current examples of carefully planned and legal medical discoveries. Recently, the first baby was born through a cadaver uterine transplant in Brazil, similar to the recent live uterine transplants being conducted. There are also new blood tests to detect various types of cancer. Rao’s point was that there are many scientific breakthroughs happening that actually have meaning and can make an impact on society. “I cannot think of a good reason to do germline editing, and I’m sorry but blue eyes and blonde hair just doesn’t do it for me,” she said.

Looking forward, Rao believes that it could be possible to use CRISPR in such ways, but it would have to be for a very in-demand affliction. The disease would need to be dominant and have no way of being able to prevent it in a child. These conditions, also lining up with someone who’s physically able to reach a childbearing age, would likely be a very rare disease and not have a strong enough demand for a cure. Typically, IVF can get around diseases as the cells can usually be screened and selected for implementation.

Though most seem to be opposed to Jiankui’s actions, some are in support. Michael Deem, a bioengineering professor at Rice University, has been suspected of being involved with He Jiankui, as Jiankui is a Rice alumnus. It is not known how in-depth his participation goes, but he claims this is like modern-day vaccination. George Church, a geneticist at Harvard University, also defended gene editing in a quote told to Associated Press, “I think this is justifiable. [HIV] is a major and growing public health threat.”

Looking forward, is it possible that the same thing could happen in the United States? Theoretically, anyone could be doing experiments similar to this. If it’s not written down, it’s not regulated. The Broad Institute at MIT is one organization that has patents to the plasmids and are therefore able to supply tools to others to use CRISPR technology. Their screening for who can buy the reagents is not very in depth. The future of gene-edited babies could be more imminent than we think.

Want to learn more? Click here to hear about the panel discussion!

http://www.wbjournal.com/article/20181205/NEWS01/181209976/wpi-professors-raise-ethical-questions-on-crispr-breakthrough